Core values, principles, and better communication

Also, don't get caught fixing communication with org changes.

Act One, Scene One: The Org Chart

Fade in: the Chief Boss Executive, Dave, stands in front of a whiteboard in a corporate conference room. The whiteboard is covered with a hand-drawn, elaborate organizational chart full of boxes and lines, names and job titles, and notes about the diagram’s complicated structure.

Pull back to reveal a room full of executives slumped in chairs. Many are staring into the screens of their phones, others are typing vigorously on laptops, and a few are staring off into space.

Cut to a close-up of Dave’s hand drawing dotted lines between several boxes while a voiceover explains, “For the time being, we will have Marty report to Jane but keep a dotted line structure to John.”

Cut to Jane and John Doe, no relation, exchanging glances.

Cut to a closeup of the exasperated face of an executive who mouths, “A dotted line matrix?!”

Cut to a close-up of Marty slumped in his chair, head in his hands.

Pull back to reveal the whole room, and then slow zoom to the whiteboard, which is now a cluttered mess of solid lines overlapping dotted lines.

Cut to a ground-level view of the whiteboard, looking over the shoulder of a woman sitting in the back of the room. The camera pulls back until we can see the back of the woman’s head as she slowly raises her hand.

Cut to Dave drawing yet more lines between boxes on the whiteboard. The woman clears her voice from the back of the room, “Aherm.”

Pan to the executive’s face. He looks annoyed as he turns his attention to the woman at the back of the room.

Dave: Yes, Debra?

Cut back to the view of Dave from behind the woman, her hand still raised. From a distance, we see him raise a single eyebrow.

The camera pans around the woman, stopping on a tight closeup of Debra’s face.

Debra: With all due respect, Dave, I’ve lost track of who I report to in this whole mess you’ve drawn. From way back here, it kinda looks like I have the same job and report to the same people as Marty. Or, maybe Marty reports to me and Jane and John? Or maybe TBH, whoever that is?

Cut back to Jane and John Doe, no relation, exchanging another glance.

A dual screen appears: Dave on the left and Debra on the right.

Dave: Obviously, Debra, you don’t report to a to-be-hired. Unless we haven’t hired that person yet, in which case you will dotted line to…um…well, yourself.

Debra: That’s crazy, Dave. If I don’t understand it, how the hell am I supposed to explain this to my team?

Pull back slowly while a murmur erupts in the room, with various executives chiming in.

Exec One: Yeah!

Exec Two: What she said!

Exec Three: Bubbles!

Cut back to Dave, the Chief Boss Executive, with a giant smudge of dry-erase marker on his left cheek. He motions with two hands, palms facing down, for everyone to remain calm.

Dave, shouting: Everyone remain calm!

Pull back to see the whole room in chaos. Executives in groups of twos and threes are gesticulating wildly and talking over one another while the Chief Boss Executive vainly tries to restore order.

Cut to Debra’s empty chair, swiveling.

Fade to black.

Organizational woes

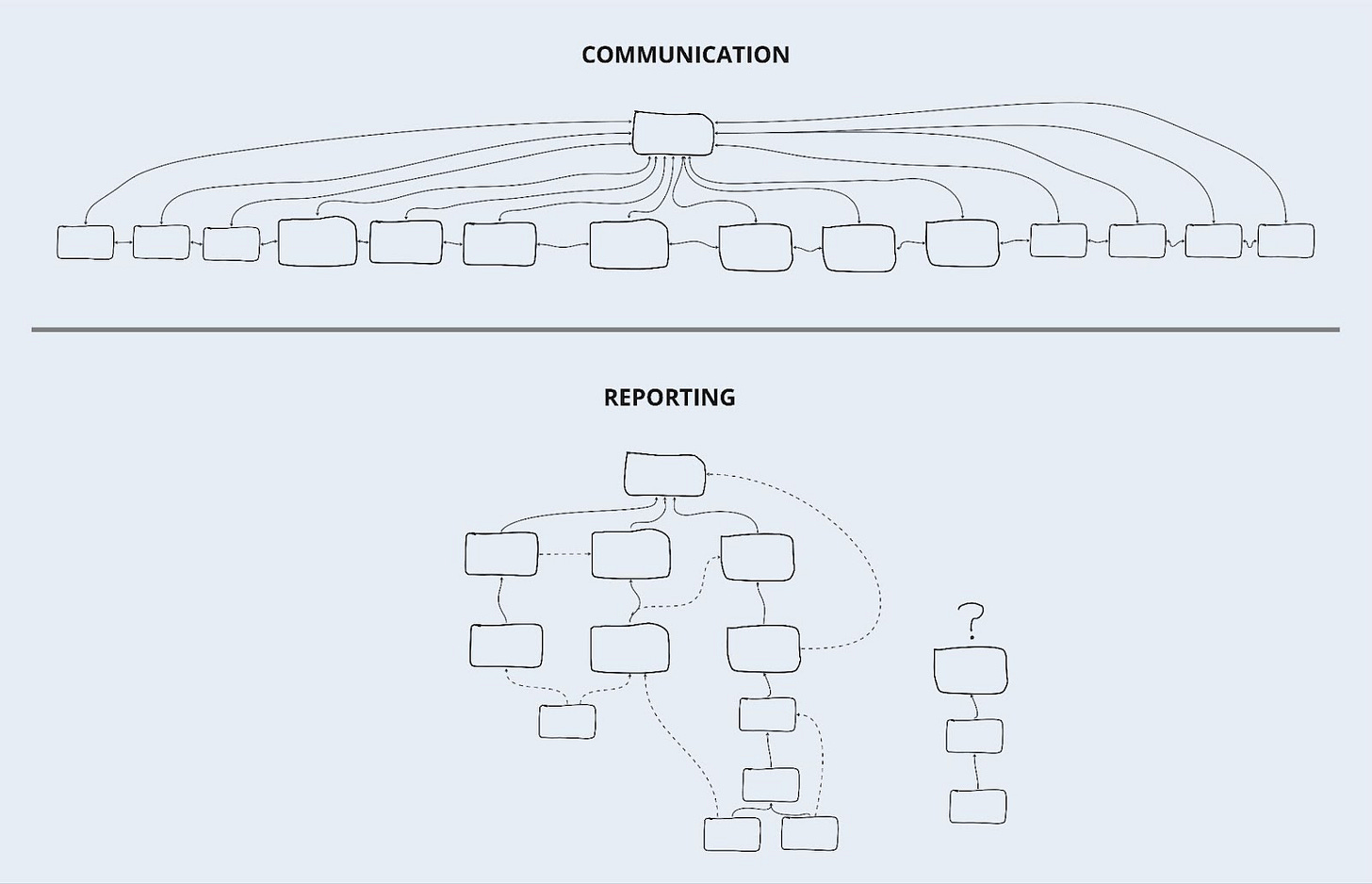

Most companies create a reporting structure when they mean to design a communication flow.

When your team is small, communication is simple. When something needs doing, people talk to one another and get it done. Slowly, team members specialize and delineate their responsibilities. Communication gets a little more complicated, but you’ve hired smart, competent people, and they figure it out.

Later, reporting structures substitute for communication strategies as new members join and the team grows. The substitution shouldn’t come as a surprise.

We expand our teams to solve problems the existing team lacks the capacity or capabilities to solve. When that expansion reaches a certain pace, companies add a human resources function to supervise the expansion and make sure we follow laws and regulations. The demands of human resources mean appointing hiring managers. The hiring manager writes a job description and posts it. The job description advertises the skills that solve the problem you’ve encountered and adds the missing skills or capacity to your team.

New team members rely on their hiring managers to help them get started, figure out the job, and learn what they need to know to be effective contributors. We call those team members individual contributors. Without specific intent, you’ve established a hierarchy in your org, which is now comprised of managers–who have more responsibilities–and individual contributors–who concentrate on narrower areas of responsibility.

I’ve never purposely designed a communication style based on a hierarchy and told people, “Before you talk to me, make sure to talk to your manager, and have her talk to her manager, and have her manager talk to me.”

I hold strong core values–openness, honesty, and transparency–contrary to that communication style. These principles are the foundations of the operating model I enact in my teams. I expect people to communicate with clarity, consistency, and transparency. I gather the team to write down core principles to guide our operating model and encourage them to follow those expectations.

Nonetheless, some of my teams still developed communication channels more closely resembling our org chart than my principles-based ideal.

Consider the figure below. The intent is clear: All team members should be on an equal footing when communicating, sharing information, solving problems, or giving and receiving feedback. The team’s structure evolved slowly into something disconnected from that intent.

Organizations evolve. Some team members talk to one another more than others, perhaps driven by something as simple as the day-to-day demands of their job’s responsibilities. At first, it may appear as though communication is flowing organically and efficiently across the organization. Conversational expedience deepens the grooves, and soon, a telltale symptom emerges: managers spend more time than they’d like repairing miscommunications and adjudicating disputes.

Here, I assume good intent from all participants, but the reality is sooner or later, you will hire two people who don’t like each other. In the past, I let these mismatches linger within my teams. Now, I recommend making the tough decision to let one of them go, usually the one I have to spend the most time convincing to cooperate with the other.

Nothing is stronger than a team who genuinely like each other.

Focus on communication, not organizational structure

I’ve succumbed to the temptation to fix my team’s communication issues by making organizational changes and tinkering with roles and responsibilities. In the dramatization, our Chief Boss Executive, Dave, worked on the faulty assumption that the best communication occurs between people organized into a reporting chain. His dotted-line reporting resulted from knowing that two people should be talking to each other, and a faulty reporting structure caused their inability to communicate. A poorly designed organizational structure may contribute to poor communication, but rarely is it the root cause.

Dave and Debra butted heads because he thought the org structure would magically clarify the team’s roles and responsibilities, and she saw how the org structure only added to the confusion.

In later attempts, I left the organizational structure alone and started by clarifying our core values and principles. I tested how I wanted communication to work by figuring out how to roll out the core principles and worked back from my desired outcome: everyone can repeat our communication core principles from memory. I knew this would require patience, persistence, and repetition. I convened a standing meeting that evolved into a “ core principles chalk talk,” where we constantly reinforced the communication principle.

Core values and principles

To fasten tightly,

Core values work best when all

Believe in their strength.

-Haiku Master, 21st Century

Core values are what you believe. They are the tenets of your life about which you do not compromise. Some examples, borrowing from my own, are openness, honesty, transparency, integrity, and accountability.

If values define what you believe, then core principles describe how you use them to operate your teams. Unlike core values, which are constants, principles are situated within the context of your business, so that each circumstance might require different core principles.

If you want open, transparent communication, you must define it as a principle within the organization, especially if your approach is unconventional. For example, if you don’t plan to form an organizational hierarchy and want everyone to have equal access to information, you must define this as a principle.

Suppose your core values espouse openness and transparency. In that case, operating on a strictly need-to-know basis creates a cognitive dissonance that will upend your organization, regardless of any structure you put in place.

Here’s an example of a Core Principle:

Powerful communication relies on clarity, consistency, and transparency.

We expect teammates to communicate freely and openly, unconstrained by reporting structure. We optimize for clear, consistent, open communication and design our organizational reporting structure, job titles, roles and responsibilities, team composition, objectives, and measures accordingly.

We don’t build teams or organizational structures and force communication through those artificial structures.

Every team member has permission to speak up, regardless of role or title, and we have an obligation to listen with openness and curiosity.

Some information is sensitive or confidential and cannot be shared broadly. Be ethical in testing the boundaries of what can and cannot be shared to make withholding information the exception, not the rule.

Flat organizations and radical transparency

But can’t you solve this problem using the proper organizational structure, like Jensen Huang did at Nvidia? According to Huang, he flattened the org chart, has 60 direct reports, and estimates he’s removed seven layers of hierarchy from his org.

While having 60 direct reports makes a good headline, what I find more compelling is how he designed communication. He doesn’t do one-on-ones but has an open meeting with those 60 leaders where he communicates to everyone at the same time. Structure the organization around this type of communication, not the other way around.

I don’t do 1:1s - Jensen Huang

Will this work for your organization? Maybe, but I’d caution you to think about it as you should about the Spotify Model for agile development. Some concepts might work for part of your organization or a subset of your teams, but none of them will work without careful adaptation.

Ray Dalio famously ran his company, Bridgewater Associates, as an idea meritocracy using radical truthfulness and radical transparency. The communication principle above approaches transparency but certainly doesn’t go as far as Dalio’s model at Bridgewater because a more radical approach wouldn’t have worked in the organizations I’ve run.

You must adapt any model to your organization, and that’s why I rely on core principles instead, as they demand adaption. It’s easier to take a model and apply it prescriptively–I see people try to do this all the time with Spotify–but core principles derived from your core values are, by definition, a blank slate.

There is nothing to apply prescriptively.

I’m sorry I made fun of Dave

Dave is doing his best. Building effective communication is hard. Contorting an organization’s shape to fix pockets of miscommunication appeals as a quick fix, and it might work temporarily. However, long-term fixes need a more robust foundation, which we find in values and principles.

Great article, food for thought as well. Highlighting the difference between communication paths and organization structures and why driving core principals are required regardless of what org and comms structure used is quite useful.

What great food for thought and guidance! Each of the principles you mention need “unpacking” in my opinion. Especially as modern teams are often culturally diverse and your model - I assume - must cater to everyone. Thanks for the clever way you presented it too, lights, action!