I never signed up for this: a product manager's origin story

Congratulations! You're a product manager!

I never signed up for this: a product manager’s origin story

In the fall of 1999, newly graduated after an extended collegiate career, and at the conclusion of a long bike racing season, I gave up my cushy bike shop gig and took a job in Silicon Valley. A friend, let’s call him Zach, told me about a tech company in San Jose hiring “anyone with a pulse”, a common occurrence during those heady dot com boom days.

Jerks, whose successors would later earn the pejorative “tech bros”, frequented our bike shop looking for high-end mountain bikes that “would look good on my Hummer’s bike rack”, with cost seemingly no object. Clearly, these companies had more money than sense. The people they hired certainly did.

One by one, our little low-income hardcore cycling community fell to temptation. A friend took a job selling 56k modems for 3Com. Another friend wound up driving for WebVan. Yet another took a job doing marketing for some soon-to-be-bankrupt company, whose name I can’t remember. (Later, after being laid off by the tech company, he would take a job hauling Aeron chairs and other furniture from downtown and SoMa offices as these companies went bankrupt and liquidated their assets.)

I was living in a South of Market warehouse with a motorcycle mechanic and his hairdresser girlfriend, another bike racer and his chef girlfriend, and a revolving door of randoms who occupied the cramped loft spaces the mechanic had built along one long wall. In all, there were 7 of us sharing a single bathroom. I needed another option but could afford little else on my bike shop hourly wage.

The lure of a (very) low five-figure salary was compelling.

Zach made the connection, and I set up an interview. I showed up to a glossy building in downtown San Jose in an ill-fitting dress shirt, ugly tie, and slacks mismatched to my sportscoat to meet with people wearing shorts and t-shirts. No one seemed to know for which job they were interviewing me, and it was hard to tell who was in charge. One of my interviewers, working her first day at the company, showed me around as though I’d already been hired.

Although I had no technology experience, a nice person, let’s call him Sachin, gave me the job anyway. In a few days, a packet arrived in the mail with an offer letter, information about health insurance, and a slick brochure that describes the company and what it does. I read it several times, unable to decipher the murky language or determine a corporate purpose.

I signed the paperwork; my first day was late September.

The name of the company was RemarQ Communities, Inc., and to this day, I don’t know how they made money. Somehow, I still have the logo coffee mug.

I was hired to do technical support for the RemarQ website, where we “curated” NNTP Usenet newsgroups, a fact that made nearly all newsgroup moderators irate. Their anger stemmed from the fact that newsgroups were militantly noncommercial, and they perceived RemarQ as violating those anti-commercial principles and stealing their communities’ intellectual property. I sided with the moderators on this point but also recognized they were fighting an unassailable tide. These newsgroups were precursors to the vapid, toxically commercial social networks of today.

In no time (and by no time, I mean just after I finally figured out how to turn on my laptop, an old IBM Thinkpad with a weird press-hold-slide power button unlike any power button on any appliance I had ever switched on), I learned how to use a piece of software called a Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) server. More accurately, I learned how to use the LDAP client and manipulate data stored on the server. Some other much more capable person had set up the server.

This education took place over October, November, and December, or CYQ4, as it came to be known; it would be months before I caught on to even basic corporate jargon.

Then in January 2000, CriticalPath, a company that sold hosted email at a time when most companies ran their own email servers, acquired RemarQ in order to “offer customers a robust integrated messaging platforms”, a comically ungrammatical phrase that was essentially meaningless1. CEO Doug Hickey gushed that Critical Path would now be “the only provider of complete end-to-end Internet messaging solutions”, a conclusion he reached without, I suspected, talking to a single newsgroup moderator. He clearly misunderstood that a substantial proportion of his new “customers” used newsgroups primarily to look at porn. Ah, the Internet and its end-to-end messaging solutions.

While I was busy learning LDAP and curating newsgroups, CriticalPath had been busy buying an Irish company called Isocor, purchasing them in October 1999 for nearly $300M in stock2. Isocor built LDAP directory servers, making money by selling to large enterprises and telecommunications companies, along with a new technology called a meta-directory, which synchronized data spread across LDAP directories and relational databases under the premise that a single, consolidated representation was better than a disjoint representation. The meta-directory product was cleverly branded “InJoin” for reasons I am sure you can guess.

Congratulations, you’re a product manager

I lived about eight blocks from CriticalPath’s San Francisco offices, but for some inexplicable reason, they required me to continue riding my motorcycle to San Jose in order to work in the RemarQ office. Fall had passed, and riding an hour through that winter’s frequent rainstorms sucked. One day in February, shortly after arriving at the office in San Jose, I was asked to attend a meeting in the San Francisco office. I hopped on my motorcycle and rode back north to The City. Once arrived, I headed into a conference room where my boss’s boss waited for me. I was pretty sure I was about to be fired.

Instead, she started asking me about what I did with genuine curiosity. I explained to her my job doing technical support for the website and the newsgroups, an intensely boring task, and how I was, in my spare time, using the LDAP client to help another team organize the way newsgroups were presented to users of the website. When I said, “LDAP client”, she leaned forward in her chair.

She said, “So, you know LDAP.” It was a statement, not a question.

“I’m learning,” I replied.

“Good. Congratulations, you’re a product manager in the directory services team.”

I was baffled. I had no idea what that meant and didn’t have the heart to ask, overwhelmed by a fear of looking stupid.

“We need you to go to Dublin and meet the team in a couple of weeks.”

Dublin is a small city in San Francisco’s East Bay. She meant the one in Ireland.

I didn’t have a passport or a cell phone, I barely knew how to work my computer, and had no idea what a product manager was or what I was supposed to do. But I was going to Ireland, and I was going to manage a product.

Barely had a clue

I dove in and started doing research. The entire directory services team was in Ireland, but there were some product managers in the San Francisco office, so I started discretely asking what they did and how they did it. I learned I was supposed to come up with a product roadmap and write some product requirements documents (PRDs) so that we could plan the next release. One of the product managers lent me a PRD he’d written for a messaging product, and I shamelessly copied the structure and content. I made a PowerPoint presentation summarizing the high points and drew a timeline representing the roadmap.

I read this book while Archie patiently helped me understand why customers used directory services. I made plans to take Pragmatic Marketing’s Practical Product Management course. I read product documentation, and market research reports from analyst firms like Gartner and the Burton Group.

I made only a single but fatal mistake: I didn’t talk to any customers.

In March, I flew to Dublin, which, save for a road trip to Ensenada, Mexico, was my first time traveling outside the US. I met with the team, who were very nice and treated me to pints of Guinness at the end of each day’s meetings. I dazzled myself by drawing on whiteboards, trying to illustrate key points from the PRD. The engineering manager and architect humored me, showing me great kindness by not revealing how appalled they must have been by this utterly clueless person who’d shown up to tell them what to build into a product they’d been caring for since its beginning. The planning was an utter failure (I wrote about this recently here). I flew home to San Francisco, absolutely smitten with Dublin and entirely demoralized, certain my short-lived career as a product manager was shortly to end.

Again, I wasn’t fired.

The engineering manager showed further mercy, agreeing to twice-weekly conference calls where we discussed product requirements and priorities while the dog that lived behind a nearby pub barked incessantly. He gently encouraged me to speak with some customers. Back in San Francisco, I received mentorship from CriticalPath’s product management leadership, especially Sue Barsamian, Sharon Weinbar, Paige Cattano, and Alex Rubin.

Two months in, I barely had a clue, but I had something much better–people around me who cared enough and took the time to show me the ropes, a lesson I carry with me to this day.

Dot com goes boom

In April, the NASDAQ tanked, falling 25% in a single week. The dot-com bubble, of which CriticalPath was a case study, had finally burst.

In what turned out to be a desperate attempt to boost revenue growth artificially, CriticalPath acquired another directory services company called PeerLogic in August of 2000 for an astonishing $400M3. PeerLogic, like Isocor, also sold a directory product, with the companies often directly competing for customers. The plan was to integrate the two directories, which is something CEOs say in press releases when they have no other explanation for why they are buying yet another company for a lot of money that does exactly the same thing as a previous expensive acquisition.

While probably not great for CriticalPath, the PeerLogic acquisition worked out amazingly for me. My new boss was Ian Lakie, a warm and gregarious man from the North Sea coast of Scotland. He was exactly the kind of boss I needed–patient, kind, and wickedly smart. To novice me, it seemed like he knew everything about the products, the market, our customers, our partners, and how to do product management.

He took me under his wing and taught me the foundations. I learned how to talk to customers and pick out nuggets from their answers, do quality market and competitive research, and plan a release full of differentiating features. I learned how to set expectations for myself and others. I presented roadmaps (wow, did I learn to hate roadmaps!) and developed OCD about the visual aesthetics of my PowerPoint presentations. I also learned not to be too greedy, to push for ambitious releases on aggressive timelines but recognize when it was time to trim so that we could push products out.

I don’t remember learning or using a particular software development philosophy. I suppose we just used what is now pejoratively waterfall. And unlike product and development teams of today, where the methodology is discussed, implemented, refined, refined again, and adjusted to the individual needs of each development pod or scrum team—we must use agile and kanban boards, or scrum boards, and we must point, or we don’t point, and for goodness sakes shift left!—I don’t recall much discussion of the topic.

I used that template from the borrowed PRD to establish some background and build the business case–there were plenty of discussions about business cases– for what I was proposing we build next.

In between all of this, Ian introduced me to English football at Elland Road, home to Leeds United Football Club. I’ve been a supporter ever since.

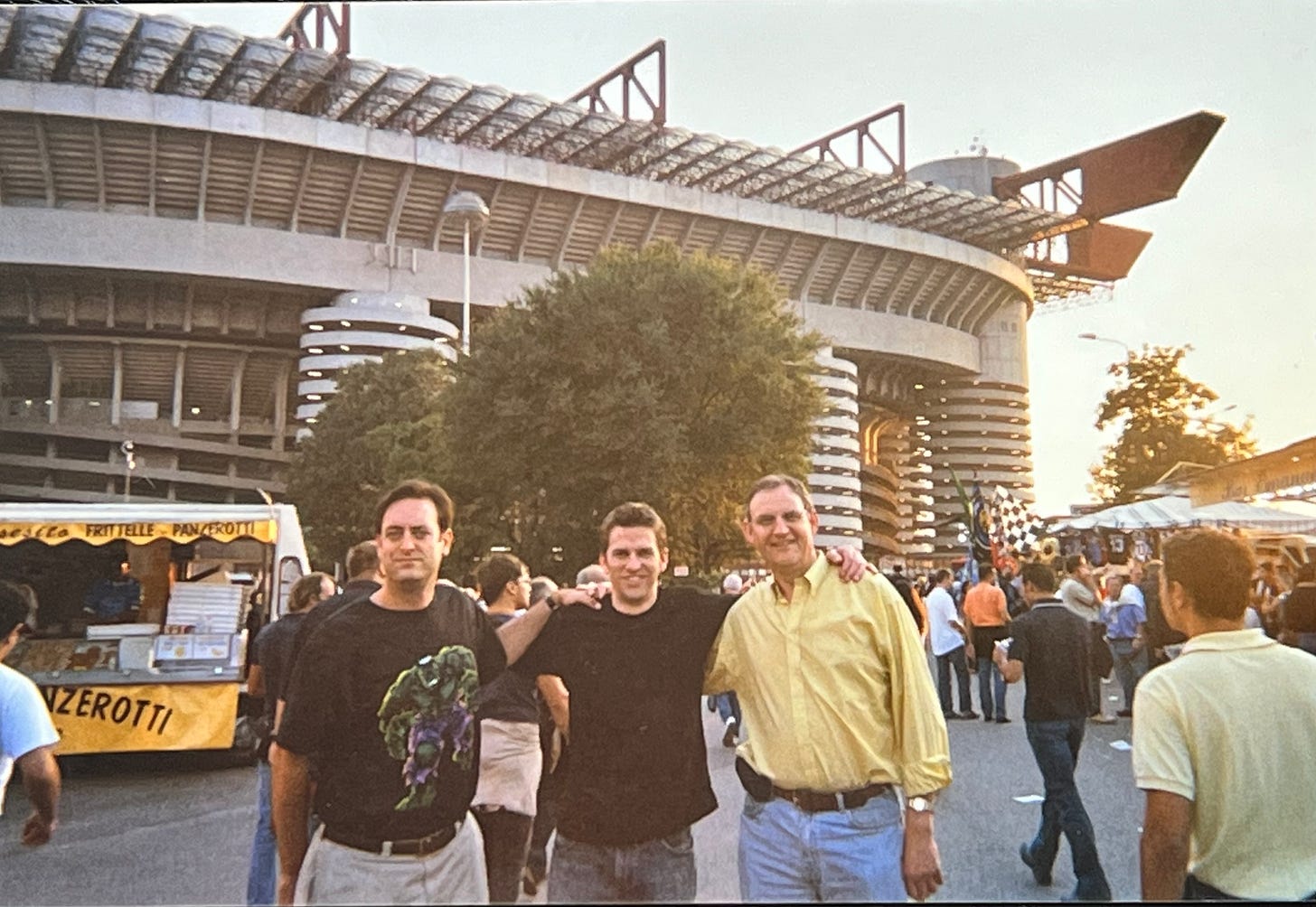

We traveled to various stadiums–Anfield in Liverpool, the San Siro in Milan, and Silk Road in Macclesfield–to watch a sport I played as a boy but utterly misunderstood as a global phenomenon.

I was starting to have fun.

On the critical path to CriminalMath

Going into the fall of 2000, CriticalPath was still riding the stock market to a nearly $4B valuation. But the email business was hemorrhaging, losing money on every mailbox hosted for a customer. Every day, new servers and storage were delivered to the loading dock behind the office, ticking up our costs another notch. This presented a conundrum to the company’s leadership: we had to sign up more customers to grow the business, but with every customer we signed up, the business became harder and more expensive to run.

The enterprise directory business into which I’d been absorbed hummed along off to the side, actually turning a profit. But it wasn’t enough to offset the losses from the messaging business, which was CriticalPath’s main focus.

By October, company executives buckled under the pressure and began overstating revenues and submitting false earnings reports. In February 2001, CriticalPath was forced to restate those prior earnings reports4. Executives were fired, and some were arrested by the FBI. The SEC investigated and imposed sanctions5. Outside consultants arrived to investigate and rectify the accounting mess. In February of the following year, one of the arrested execs, Dave Thatcher, cut a deal with the FBI, selling out other executives in exchange for a guilty plea and a reduced sentence. Cue more arrests by the FBI, convictions, and jail time.

The stock was freefalling. Investors and stockholders were left holding the bag. It didn’t go any easier on employees. Twenty-somethings who, at the height of the company’s valuation, had vested and exercised their incentive stock options and were left with six-figure tax bills, which they were unable to cover with cash proceeds from selling their increasingly worthless stock. Within two years, CriticalPath’s stock price dipped below $1 and was delisted from the NASDAQ.

I was still learning to be a product manager, and all around me, chaos was happening. Conversations with customers and prospects turned from discussions about products, features, roadmaps, and competitive differences to questions about executive conduct and accounting scandals, things about which I knew nothing and about which I couldn’t comment even if I did. Product managers are often the face of a business, and my prize for putting on that face was having my credibility and integrity called into question on an almost daily basis. I naively thought it couldn’t possibly get any worse.

I was wrong.

By the time I left for Sun Microsystems nearly four years later, traumatized and demoralized, I had survived eight rounds of layoffs, holding watch while the desks around me emptied until, at one point, I was one of a small handful left occupying an entire floor of the office we leased in Hills Brothers Plaza.

When I grow up, I want to be

When I grow up I want to be,

One of the harvesters of the sea,

I think before my days are done,

I want to be a fisherman.

“John the Fisherman”, by Primus

If you happen to go to a five-year-old’s birthday party and ask the kids there what they want to be when they grow up, and even ONE of them says “software product manager,” please message me immediately.

I have a job for that kid.

The data suggest a substantial increase in the number of product managers and their strategic importance to companies of all sizes. One oft-quoted informal study shows a 32% increase in the number of product management jobs between 2017 and 20196, which continues a trend extending back two decades. LinkedIn’s product management groups boast tens of thousands of members, with job listings and hiring stats growing steadily for years.

Software runs the world, and product managers run the engines building that software, and yet we don’t have a generation of kids preparing for their college educations with the mindset that when they grow up, they want to be product managers. Our education system provides clear tracks into software development, project management, design, and marketing. But a product manager’s education tends to be ad-hoc, and we are expected to acquire, develop, and refine skills on the job. We rely on mentors, often with day jobs of their own, to teach us critical parts of our jobs. [Editor’s note: A handful of universities now offer master’s programs in product management.]

I went from nothing to product manager in about two years, a time which I think of as my “Master of Product Management”. Placed in the context of skills progressing from awareness to proficiency to expertise, I barely cracked awareness. The thing is, with the right care and feeding, I think anyone can achieve proficiency, or even a level of mastery, in the same amount of time.

We accept product management as this mythical combination of art and science, revealed the way a seeker finds enlightenment by combining the close study of, say, blood chemistry with frequent visits to sweat lodges. Product managers discover the enigmatic combination that makes products great and worth building, even while chaos swirls around them. Especially while chaos swirls around them.

But discovering the combination happens through trial and error rather than education. Despite a wealth of reading on the topic, I suspect most product managers, when asked in their private and honest moments, would shrug while admitting they don’t know exactly how they do it even though it getting done is an observable fact.

Product management chooses us; we fall into it opportunistically, learn a basic skill set, and progress from there.

I wanted to tell my origin story because I believe many (most?) product managers relate to this “accidentally a product manager” experience because it so closely mirrors their own. I faced extra challenges in the form of a bursting dot com bubble crushing business opportunities, the craziness of working inside a failing company, and watching unscrupulous executives go to jail.

But even without those challenges, the road to a successful career in product management would still have potholes and unexpected turns and would largely be a DIY exercise.

~~~~~~~~

What did you experience becoming a product manager?

How did you acquire the skills you needed to be successful? How long did that take?

https://www.internetnews.com/it-management/critical-path-grabs-messaging-firm-remarq/

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB940514435217077581

https://www.itworldcanada.com/article/critical-path-acquires-peerlogic-in-us400-million-deal/34690

https://www.computerworld.com/article/2591497/e-mail-outsourcing-firm-moves-to-restate-results.html

https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/34-45393.htm

https://medium.com/agileinsider/incredible-growth-in-demand-for-product-managers-in-the-us-but-not-necessarily-in-the-places-youd-936fec5c1932

What a great story! Thank you for sharing.

While we had different paths, so much of this rings true. I remember being at Schwab and looking around at all the empty desks after the layoffs through 2002-2004. And when I finally left and went to a career counselor, she asked if I still wanted to be a Product Manager.

"What's a Product Manager?" I asked.

"It's what you've been doing for the last four years."

Had never called it that, but I've been calling it that now for the last 20 years!