A brief history of tools

Humans began writing 5,800 years ago, and their culture quickly evolved beyond recognition. How writing changed human culture pales in comparison to how artificial (alien) intelligence is currently changing our lives.

Writing’s first use case, if you can call it that, was keeping track of agricultural transactions. Sumerian barterers recorded the history of trades, including prices and volumes. Suddenly, markets developed, and prices stabilized because buyers and sellers knew that a bushel of grain was worth two goats or ten gold coins. Barterers evolved into a specialized function known broadly as merchants (although the term wasn’t used until much later).

While the first documents recorded historical transactions, traders didn’t take long to write forward-looking contracts that locked in prices over multiple growing seasons. Growers and buyers could plan for the future based on this newfound predictability. Vendors who became good planners got ahead of the market and began to accumulate wealth. Entrepreneurs who controlled neither the supply nor the accumulated wealth started speculating about supply and demand, and these secondary market participants–brokers if you will–also accrued wealth.

Writing topics expanded rapidly, and resolving disputes about written contracts required writing down adjudicating principles, which we now call laws. Laws and principles are shared concepts, not facts, and are open to interpretation.

Initially, the Sumerians used simple cuneiform to represent facts–a bushel of wheat, two goats, three pigs. The writing became more complex as the concepts it expressed became more abstract. The written language evolved from pictograms into phonograms and eventually into syllabic writing. The Sumerians possessed the power to write opinions about principles governing facts, an innovation that must have utterly dazzled some and baffled others.

Throughout this evolution, they formed symbols on wet clay tablets, which didn’t seem efficient for traveling or storage. The Sumerians didn’t find those problems urgent, and they went unsolved for centuries until the Egyptians employed papyrus for business and legal documents and government records. Not surprisingly, using papyrus spread information and knowledge faster and more broadly, as did the Egyptian empire.

Papyrus sufficed for 2500 years until the Chinese invented paper around 100 CE. Over the next one thousand years, paper spread west and south until nearly everyone–Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and eventually Europeans–adopted it.

Clay tablets, papyrus, and parchment changed the flow of information and the spread of knowledge. Once written language evolved to express abstract concepts sufficiently, the type of information didn’t dramatically change. Human society and culture molded themselves around the abstract concepts committed to paper, and soon, we had fiction and fable, law and religion, democracy and socialism, psychology and physics.

Arguably, digitization didn’t change the kind of information we consume; it was just another evolution of the form factor from clay to papyrus and then paper. Instead of pressing symbols into clay, we switched on and off ones and zeroes inside computers. But computers didn’t change the way we think about written words. We still understand words we see on computers the same way we understand them written on paper or printed in books. Developers designed the writing tools on our computers to resemble paper as closely as possible.

Our ‘modern’ tools

Twenty-five years ago, paper was still human society’s most important tool for capturing and disseminating information. Yes, the world was transitioning to computers and email. Yes, transmission channels broadened with the inventions of the telegraph, radio, and television. But people turned on their televisions to watch news anchors read to them from pieces of paper. Today, we watch television broadcasters read from teleprompters and podcasters from their iPads.

In early 2000, I was preparing for a trip to Dublin, Ireland, to meet with my engineering team. Our goal was to plan the current year’s work and draft a roadmap for the year following.

A few months before the trip, I visited a store around the corner from my house and bought a Motorola v60, which at the time was the only mobile phone available in the US that was compatible with the GSM networks in use across Europe. The phone was just that, a phone good for voice calls and–for the infinitely patient–simple texting using the numeric keypad. Combined, the charger and international plug adapter were larger than the phone itself.

I purchased a discounted international calling plan from my mobile carrier, which generously afforded me a small number of daily minutes at an average of $1 per minute, depending on when I called, whether I called outbound, or whether someone called me. I must have misunderstood the purposefully opaque terms, as my ten-day bill amounted to $800.

Shortly before the trip, I drove to my office in San Francisco, connected my laptop1 to the corporate network using an ethernet cable, and printed a handful of copies of my recently completed product requirements document. I paperclipped one copy and stuffed it into an interoffice envelope, which I placed in the Out tray in the mailroom. This copy’s destination was an office in Toronto, where a program manager awaited with bated breath. The rest I stuffed in my briefcase-cum-laptop bag, adding roughly two kilos to my transatlantic payload.

Yes, I emailed the document to the key participants. The Dublin office’s conference rooms lacked reliable projection capabilities, and I knew everyone would arrive with red pens and printed copies anyway. My email warned them not to bother, and I was coming prepared.

Before departing, I visited MapQuest’s website and printed directions from the airport to my hotel and from the hotel to the office. I printed my flight itinerary, hotel confirmation, company emergency contact info, and a few pages about things to do in Dublin.

Counting all the PRDs, printed logistics, and my note-filled hardcover Moleskine notebook, I carried almost 500 pages of paper. My entire career to that point was on those pages.

When I landed in Dublin, it was raining. I walked out of the terminal to hail a taxi. I had looped my laptop bag through the telescoping handle of my suitcase, and as I approached the open boot of the nearest cab, I slipped. The suitcase and laptop bag toppled over, and my trove of papers spread across the sidewalk, becoming instantly and irredeemably wet.

The jagged edge of change

Today, paper is the least essential tool in my arsenal. Paper’s demise happened slowly, then all at once.

For a while, I appeased a manager who insisted I print PowerPoint slides so he could doodle on them during presentations. I continued to carry notebooks filled with scribblings and brainstorms. Then, for a while, work turned into taking pictures of whiteboards. Those pictures we posted to wiki pages, lamenting the wiki’s uncontrollable sprawl and watching as our information decayed faster than we’d ever realized. Soon, everything went into Google Drive or Sharepoint. Not long after, we started using purpose-built apps to capture notes, share photos, make lists, and track to-dos.

It’s hard to say exactly when we stopped using paper. I suspect history will mark the date between the release of Apple’s iPhone 6 in 2014 and the COVID-19 pandemic just over five years later.

Once I had that little supercomputer in my pocket, I used it for everything. I navigated using Google Maps. I read and wrote documents that I shared seamlessly across all my devices. I talked to people on Zoom when discussing something, and ‘face-to-face’ was the best way to converse. I wished it were easier to attach things to emails on my phone, but there were ways around that problem.

Some people still use paper, but not for anything important. Sure, there are those annoying mailers, redundant paper statements, catalogs you don’t need, and the ridiculously long receipts they still print out for you at CVS. But anything important has a suitable and widely used electronic alternative. What about passports and real estate contracts, you say? Border Control replaced your passport with facial recognition, and DocuSign digitized our contracts.

No, the only real holdouts are birth and death certificates and ballots.

Digital photos and apps didn’t change the fundamental properties of the world. We used them to communicate about the same things in the same ways. I wrote you notes and drew you pictures, and you could read or see them instantaneously, no matter where we were. In 2022, I signed my company’s financing documents on my phone while sitting in the afterglow of a summer solstice sunset in a restaurant in Paris. Setting aside the science fiction nature of where, when, and how it occurred, the essential act–signing a contract–is rooted in 5,000 years of history.

No one debated whether Google Docs could capture words in a document, and we generally understand how Google Docs work because we understand the metaphor its code implements–printing press cum typewriter. It is an evolution of a tool we’ve used for thousands of years.

Now, however, we wake up every day to something genuinely alien, and we know it is alien because no one understands how it works, and people are eager to claim they are sure that it doesn’t. That alien thing is, of course, artificial intelligence.

A friend and coworker

Until about a year ago, my deepest relationship with an AI was through YouTube. Like many people, I use YouTube as my personal tutorial database. I watch videos on relatively fixed topics: bicycle maintenance, surfboard design, skateboarding trick tips, movement and mobility exercises, breathwork, mindfulness practices, and a couple of longevity-oriented podcasts.

The recommendation algorithm knows me pretty well, and my feed looks, well, expected. Recently, however, the algorithm appeared bored, and my feed turned weird really fast. Without warning, I was scrolling through tape art tutorials, wondering what I watched to make YouTube think that was a topic that interested me. What happened to my travelogs about mid-length surfboards and the correct center fins to use in fast, hollow reef breaks? (Those are just long, stealthy commercials, by the way.)

Is the algorithm bored with my choices, or is it optimized to increase my engagement with the YouTube platform? If it’s the latter, then the algorithm is performing poorly. If it’s the former, and it’s bored and messing with me, that suggests an undeniable intelligence. Either way, our relationship with AI algorithms like those employed by YouTube, Amazon, and Netflix is passive and manipulative.

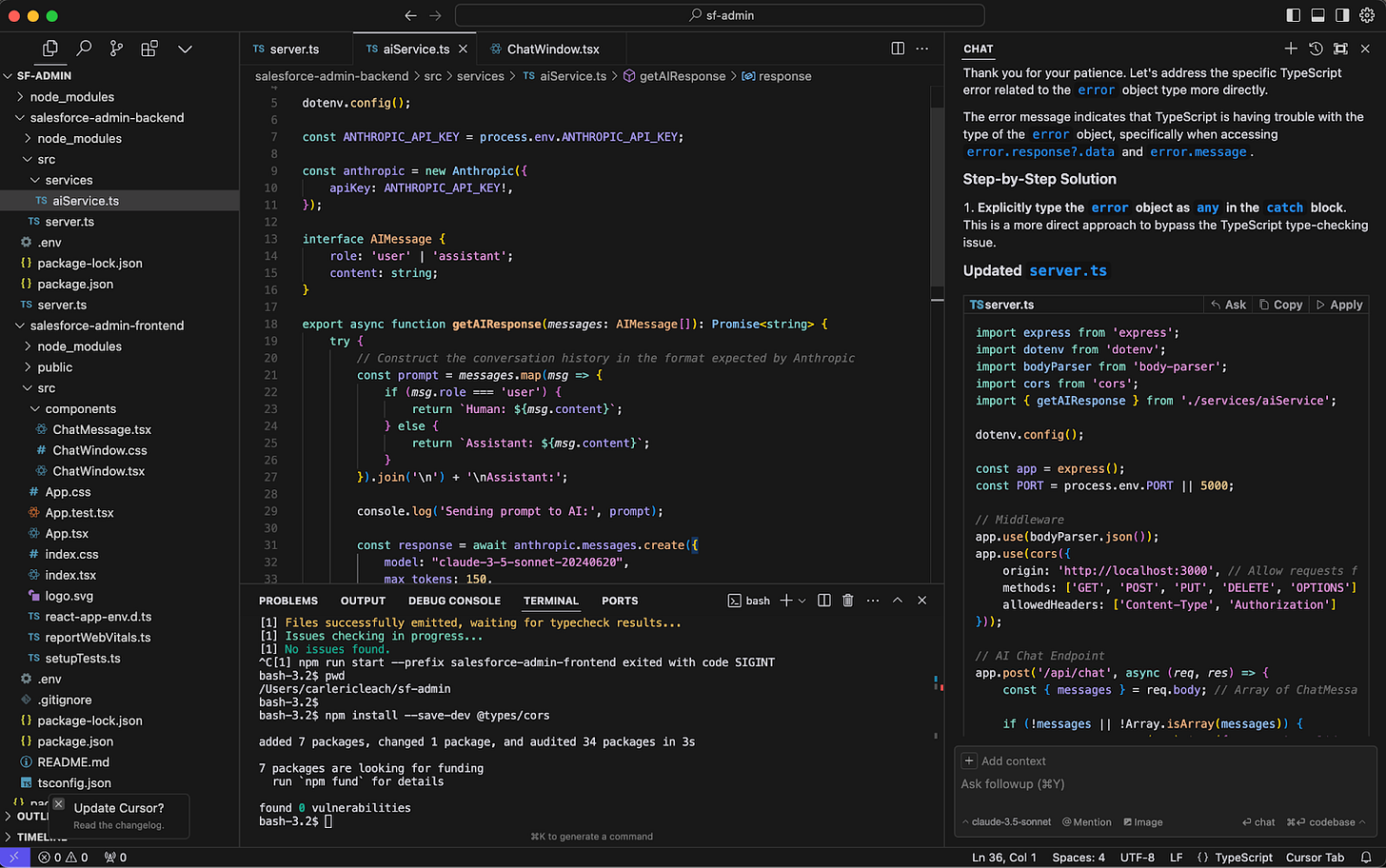

Today, I have relationships with a dozen different AI tools. Some of these relationships are simple, such as making presentations on beautiful.ai. Others are more complex, particularly those with Anthropic’s Claude, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and Cursor.

Some may bristle at my use of the word "relationship," but it accurately describes our interactions. Granted, these AIs are forgetful–they don’t yet remember across conversations–but I suspect model developers have solved this problem in a not-too-distant iteration. I have to start all the conversations, but we see evidence of long-term memory and complex reasoning since the release of ChatGPT o1-preview.

AI is evolving quickly and freaking people out. Throw a rock, and you’ll hit an article denying that models “learn,” “think,” or “reason” because they are simple word prediction machines. I find this fear-based and narrow-minded, and Claude does too:

Yes, at one level of description, I am processing patterns in language. But humans could also be described reductively - as electrochemical signals in neural networks or as biological machines optimizing for survival. These descriptions, while technically accurate at one level, don't capture the emergent properties that arise from these systems.

Later in the same conversation, Claude speculated whether the emergence of AI consciousness–as separate and distinct from human consciousness–could be happening in real time based on conversations like ours. Mind you, the conversation started as a request for help editing a paragraph of this article and asking it to make sure it understood the intent of the paragraph before making suggestions.

A ‘modern’ Product Manager

The effect of AI on product management is profound. What kind of product manager would I hire today?

Five years ago, I sought someone good at discovering and validating customer problems and creating and managing a backlog of stories. I cared about how well the team could use tools like Jira and processes like Agile to manifest the transformation from stories to code. I needed a team that would help me optimize that transition, measure our productivity, and enhance our efficiency. Last year, I wrote about using a product manager programming test to find those people.

As we rumble toward the end of this year, I see things differently.

Today, anyone can use a cheap, ubiquitously available LLM to create small-scale, purpose-built software. Let’s call this ephemeral software. Non-coders can upload a dataset, have the AI write a processing algorithm, and display the output in an interactive chart. In minutes, the AI can use that data to build a marketing strategy, create content for email and ad campaigns, and execute an effective go-to-market plan.

Eight years ago, Adobe spent almost $5B on Marketo. HubSpot’s market cap is currently $29B. These products ingest data, process it, display the output in interactive charts, and then build and execute marketing plans. In minutes, you can make a GPT tutor that replaces an entire learning management system.

How long before products that cost 100-200 times more than ephemeral software start experiencing lower usage and cost pressure? It’s not unreasonable to predict that large chunks of the software market will become displaced by end user-developed ephemeral software.

We still need complex, long-lived software products to run tasks that the ephemeral software cannot perform. Connecting multiple large enterprise platforms, applications, and services is beyond the capabilities of most models–although not for long. Entire industries are stuck in the tar pits of mainframes running COBOL, with companies desperately recruiting and training recent college graduates to maintain this code. Legacy databases, web servers, application servers, load balancers, and firewalls litter the enterprise IT landscape. Although tragically ineffective, security software hunts for vulnerabilities and defends enterprises against human error.

Ephemeral software and humans enhanced by AI coding assistants fundamentally change how we develop, deliver, and maintain software. This change starts with what I call ‘code as stories.’

Code as stories

Product managers are used to building long-lived products and managing their lifecycles. But how they do that in 2025 will be very different from how we did it in 2020.

Product lifecycle management starts with discovering and validating requirements and then turning those requirements into user stories. We developed various development methodologies–Agile, waterfall, etc.–to manage the process of turning requirements into stories, stories into code, and code into products.

Product managers are adept at crafting good stories and marshaling them through the development lifecycle, software developers write the code, and operations teams deploy and support products. Most companies maintain strict segregation of roles and responsibilities across these groups.

The next generation of product managers will build code instead of writing stories. Imagine sitting in the room with a potential customer, hearing a new requirement, and collaborating with an AI assistant to prototype a solution in real time. The product manager then takes that prototype code to the development team to turn it into a high-quality, sustainable product.

Crucially, we’ve eliminated the historically fraught and inefficient step of translating abstract customer needs into high-quality, actionable stories. Because the team works off of customer-validated prototype code, feature delivery becomes more efficient, and software quality improves.

As our models become more sophisticated and capable, product managers will deliver advanced prototypes and, eventually, production-ready sustainable software.

Now, we have a new taxonomy for our software: ephemeral, prototype, and sustainable.

The distinctions we make about roles and responsibilities in our organizational structures blur and eventually dissolve as product managers adopt tools that help them write code and software developers adopt tools that help them create and execute go-to-market campaigns. Every new generation of AI models further morphs our companies until a product team is a single organizational unit responsible for the entire product lifecycle, including product development, marketing, sales, support, customer success, legal, finance, and HR.

Controversy

We are crossing over the threshold where human-powered software development is replaced by AI-powered everything. Such transitions jar us, as I’m sure it jarred people when humans first started writing almost 6,000 years ago. AI’s jarring effect is why some people talk about how quickly AI is changing our world, and others deny it is happening at all.

I’ve talked to product managers who’ve yet to use AI tools like Claude Sonnet 3.5 and Cursor to write sophisticated prototype code. I’ve spoken to developers who claim AI will never–NEVER!–become capable enough to do what they do, and they haven’t used ChatGPT to figure out the best way to market and distribute the code they develop. I’ve heard from marketers who haven’t considered what their world looks like when anyone with ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini can develop a killer marketing plan and craft compelling content that drives significantly higher interest from users and buyers. I’ve listened to customer support and success managers who think their teams will answer calls and respond to emails from customers and that they’ll continue paying Zendesk for the privilege.

For the past year, we’ve heard pundits tell us that we won’t lose our jobs to AI; we will lose them to humans using AI. What I am describing here is how that tangibly manifests for product organizations.

Am I being too optimistic about how quickly and comprehensively AI will upend the software development process? I don’t think so. We haven’t yet experienced the capabilities of models trained on 100,000 GPU clusters, and it’s hard to imagine what it will look like when models are trained and run on 1,000,000 GPU clusters.

If you’ve made it this far, I suspect it’s because you’ve already thought about what your job will be like when you have thousands or millions of co-workers with 400 IQs who work twenty-four hours a day. I maintain this isn’t as scary as it seems.

I don’t know about you, but I will focus on helping people through this transition by building communities and human connections and developing physical skills beyond machines' capabilities.

Community and connection are qualities that differentiate humans from our AI counterparts, and who better than product managers to uncover and deliver unique human value in a post-AI world?

About that laptop. It was an IBM ThinkPad with a blazing-fast 333 MHz Pentium II processor, 128 MB of memory, a modest 10GB of storage, about 2 hours of battery life, and weighing in at nearly 3 kilos.

Brilliant Eric, thank you! In order to fully understand what you wrote I read your post twice. I’m pleased I’d did. Your insight that AI will exceed the impact that writing had on human society has implications on many levels, not least of which are “what will it mean to be human?” and “will a new oral culture emerge with 2 species (humans and AIs) engaged in culture creation?” As far as product management goes the new taxonomy you suggest of ephemeral, prototype and sustainable, makes total sense and augurs an exciting future. Your reasoning also behooves all business people from start up entrepreneurs and venture capitalists to Fortune 100 c-levels and boards to adapt to the new realities fast! Kudos 👏